Sequence classification expressivity

Comparing expressivity to learnability

This is a writeup of my miniproject for the DNN module. The source code is available on github.

It’s great work, and you clearly went beyond the brief. -Ferenc Huszár

This project investigates the expressive power of sequence classification models by comparing them to formal grammars. Specifically, I lower-bounded the complexity of languages which different sequence classification architectures can theoretically recognise on the Chomsky Hierarchy, and compared this to the languages which they empirically learnt to recognise.

Findings

Through the experiments in this project, I was able to discover:

- Learnability is a subset of expressivity

- Models can perfectly represent many languages

- Models do not perfectly learn even simple languages

- Recurrence as an inductive bias helps models approximate finite automata

- Efficient transformers are less expressive than transformers

Methodology

The primary contribution of this project is to demonstrate a separation of the grammars representable by models, and those which they learn. To achieve this, I train sequence to sequence models on datasets belonging to different formal grammar classes. I hardcode weights or use RASPy

During this project, I investigated the expressivity of RNN, GRNN and transformer architectures. Latter experiments also tested some efficient transformer architectures: linformer

Designing information retrieval datasets

The project must first empirically provide lower bounds on the expressivity of languages recognisable by sequence to sequence models. To this end, I constructed three synthetic information retrieval datasets. These datasets were dictionary-lookup tasks with keys in different grammar classes. Each dataset consisted of sequences of random symbols with a key immediately followed by a value.

- the regular dataset key was \(🔑\)

- the context-free dataset keys were of the form \(🗝️^n🔑^n\)

- the context-sensitive dataset keys were of the form \(🗝️^n🔑^n🗝️^n\)

I constructed these datasets by generating random sequences, inserting keys and then running a vectorised state machine to recognise and then remove any spurious keys. Models output whether the key had occurred, and if so what the value was. This ‘essentially’ turned sequence to sequence models into sequence classification models.

How can we prove how expressive models are?

Let the dataset \(d_g\) be a key-value retrieval dataset with keys drawn from grammar class \(g\). If a model \(m\) trained on the dataset \(d_g\) is able to perform well, then the languages learnable by \(m\) is not a subset of the grammar class \(g\).

Based on this observation, I train RNNs, GRNNs and transformers on the datasets I have constructed. Through this, I am able to lower-bound the complexity of grammar classes which are representable by different models.

RNNs struggle to recognise some regular languages

Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) are the oldest sequence to sequence models. They have an implicit bias towards recurrence: RNNs process data sequentially in order. This means RNNs mimic the operation of a finite automaton, and as such should theoretically be able to learn simpler grammars classes.

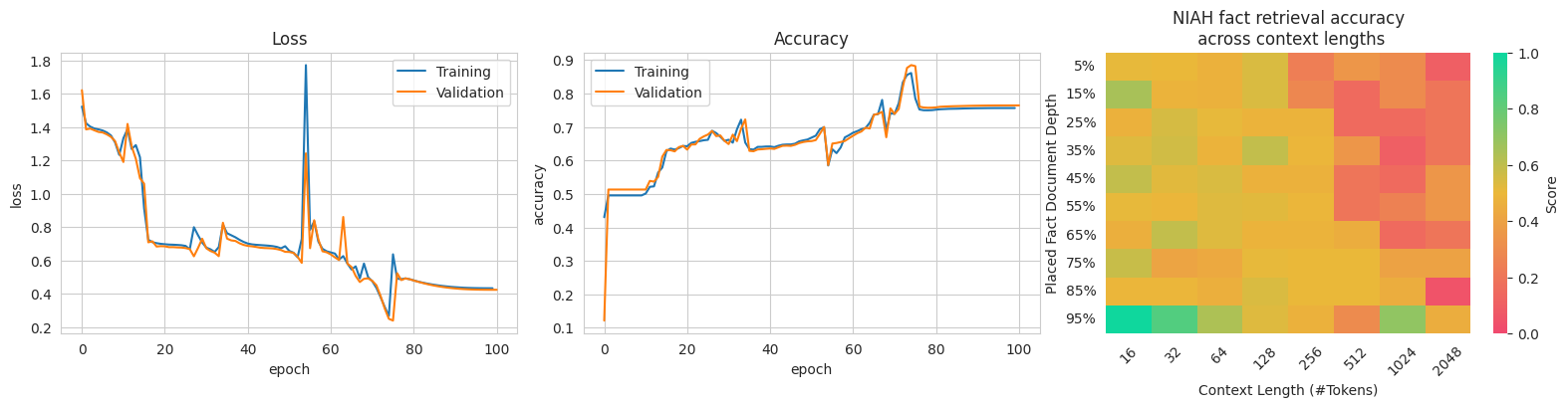

Unfortunately, my experiments demonstrated that recurrent neural networks do not consistently learn even simple regular languages. As seen in

Critically, I observed that the RNN had great difficultly with the regular language dataset. Demonstrated by it typically converging to undesirable solutions: often getting stuck at 60-70% accuracy. During testing, it did converge to 95%+ accuracy sometimes, which demonstrated that it can learn to approximate the computation of a DFA.

Given that this is a comparatively simple sanity-check, it is surprising that the RNN is struggling. RNNs obsolescence in modern literature represents these limitations.

To determine whether the inability of RNNs to learn the regular language was due to a fundamental inability to represent the grammar, I set out to hardcode the weights for an RNN which recognised the language. After many hours of maths, I was able to explicitly construct RNN weights which caused the model to perfectly mimic the behaviour of a DFA, achieving 100\% accuracy. To demonstrate that all regular languages are representable by a DFA, I then hardcoded weighs for the context free dataset. Through this, I proved that RNNs are able to represent regular languages.

The above theoretical results imply that the inability of RNNs to learn the simple regular language is due to the limitations in trainability rather than expressivity.

GRNNs recognise many languages

My analysis of RNNS demonstrated that their inability to perform was largely due to training limitations rather than expressivity problems. Gated RNNs (GRNNs) improve upon the original RNN architecture and make them more trainable. To provide theoretical justification to this, I investigated whether GRNNs and RNNs are separable by formal grammars.

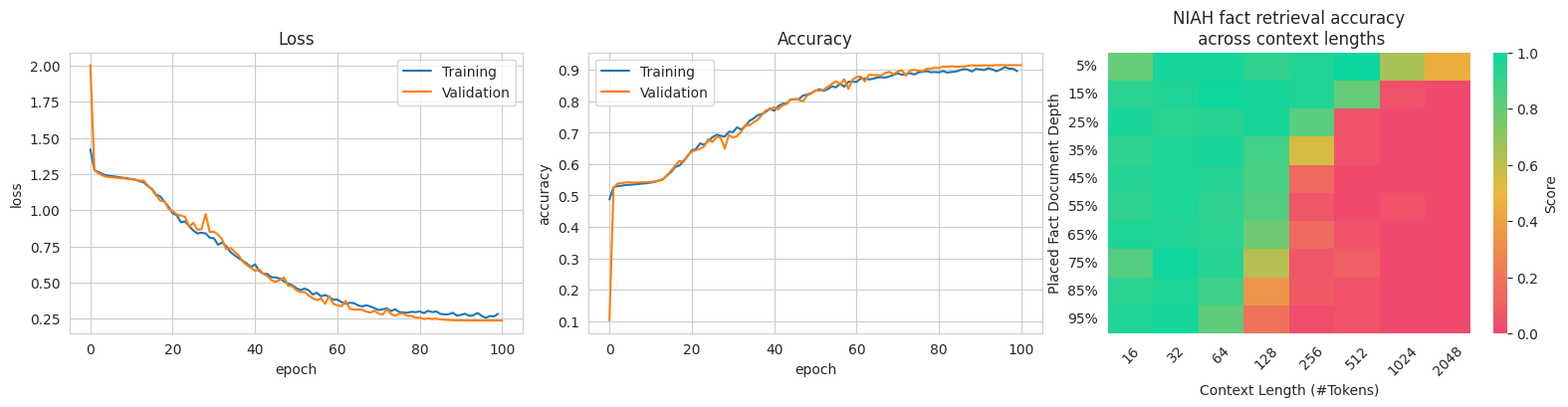

Empirically, I found that GRNNs were able to recognise regular and context free grammars to a high level. Furthermore, they took steps towards recognising context-sensitive grammars. However, they were unable to fully learn context-sensitive grammars.

Human grammar requires functionally all features of context-free grammars – and some context-sensitive features. Since I have demonstrated that GRNNs struggle to learn context-sensitive features, it is unlikely that GRNNs would be able to fully represent human language. This means that they are unlikely to be able to form the foundation for the most powerful models.

Transformers

Transformers emerged in 2019 and caused rapid improvements in SOTA across every major subdiscipline of ML. They are fundamentally different to the previous models and are based on the attention mechanism. Each token is able to directly attend to all previous tokens, bypassing the ‘exponential forgetting problem’ and removing the recursive inductive bias.

I trained the transformer all three datasets: regular, contxet free and context sensitive. The transformer was able to learn the regular and context free datasets. Furthermore, it was able to approximate context-sensitive languages. But they struggled to generalise to longer sequence lengths.

I validated that transformers are able to represent regular and context free grammars by using RASPy

Do models recognise context sensitivity or approximate them?

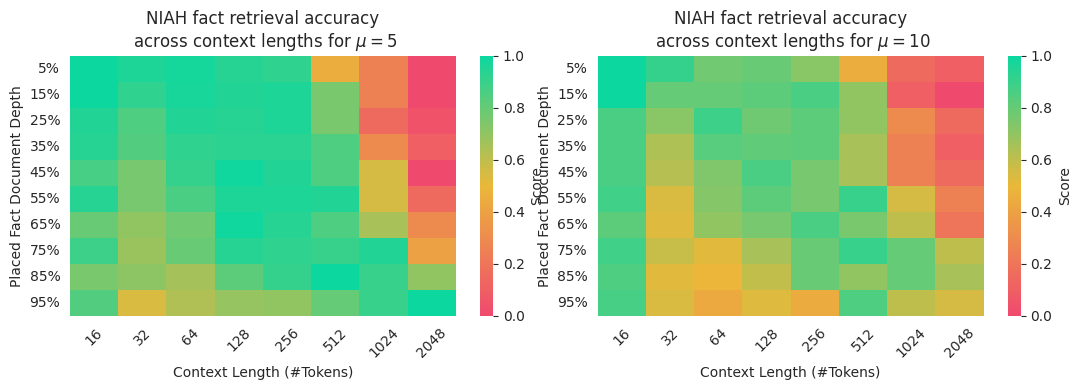

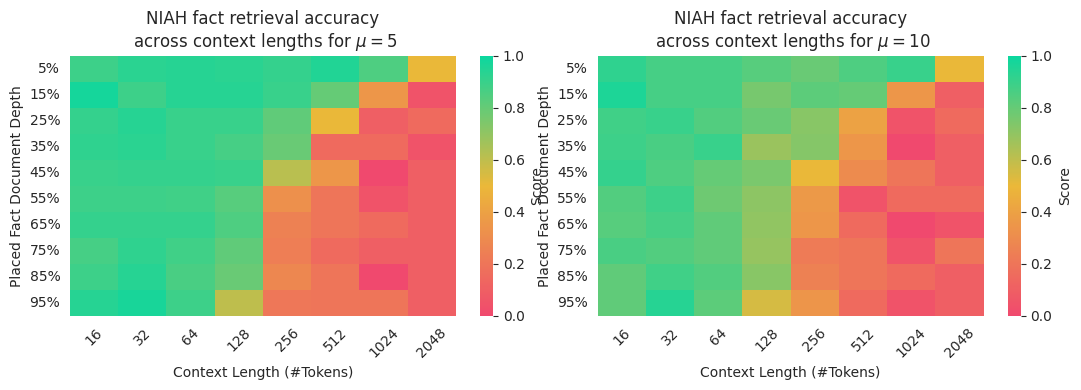

The lengths of the keys for the context sensitive dataset were drawn from an exponential with parameter \(\mu\). By adjusting the value of \(\mu\), I can adjust the distribution from which keys are drawn. This allows me to test whether the model is truly learning the grammar, or merely statistical relations. If the model has learnt the grammar, then adjusting the value of \(\mu\) will have negligible effect on model behaviour. If, however, the model is merely approximating the grammar, then adjusting \(\mu\) will move it into OOD and cause significant performance degradation.

From the above figures, we notice that transformers retained their performance when the distribution from which keys were drawn changed. This implies that they were able to better represent the context sensitive grammar.

Efficient transformers are fundamentally less expressive than transformers

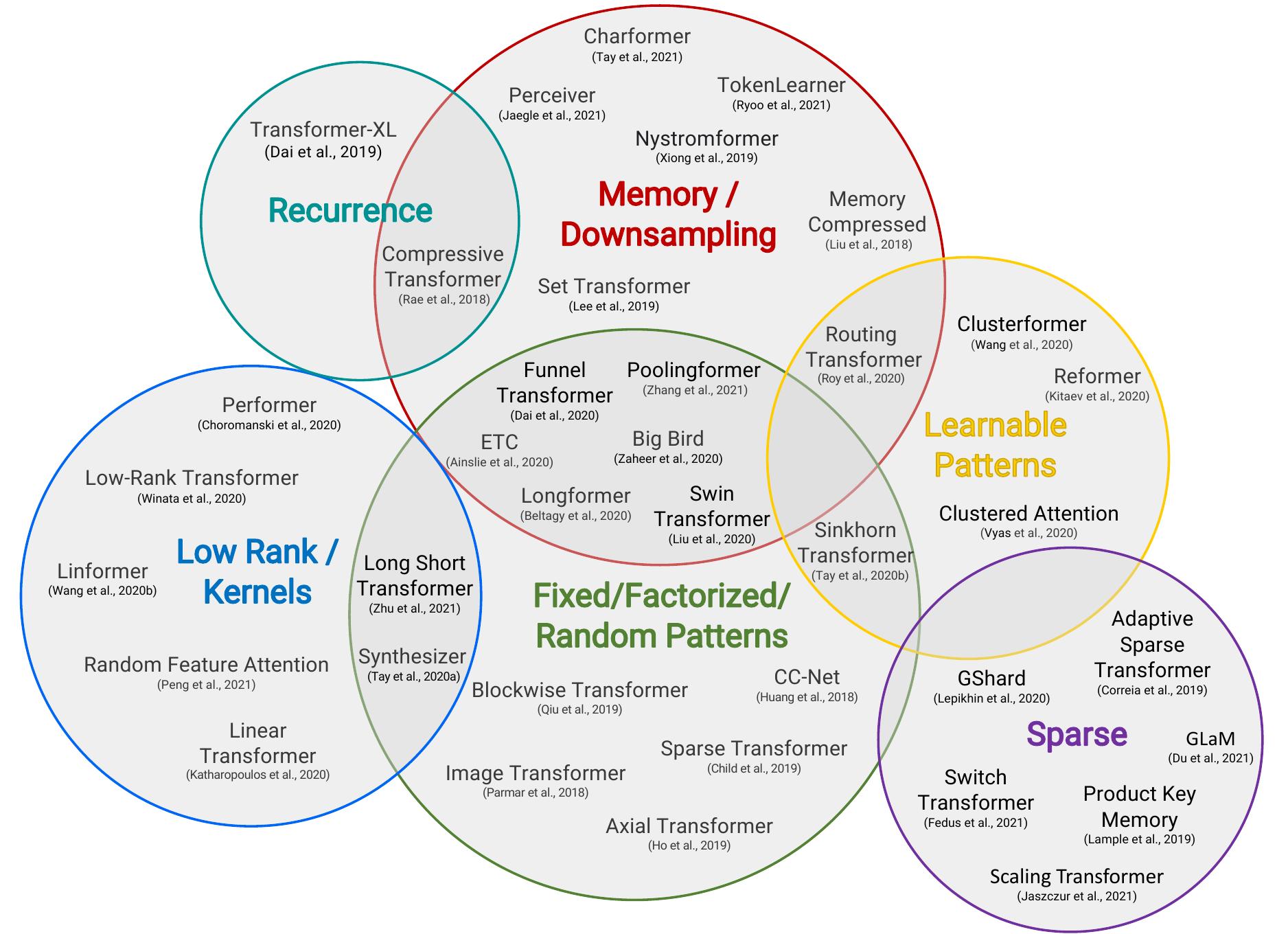

The above experiments support the hypothesis that transformers are fundamentally more expressive than other sequence to sequence models. However, transformers are also more computationally expensive. This means that much research has investigated efficient transformers. It is summarised below, in a venn diagram constructed by Efficient Transformers: A Survey

This diagram shows that there are a wide range of transformers, whose methods of increasing efficiency can be split into a few categories. I continued my investigation by selecting and reimplementing two efficient transformer architectures. I chose Linformer and Sparse Transformer since they are different types of efficient transformer.

Linformer limits expressivity

Linformers are efficient transformers. They operate on constant-length datasets and have no causal mask. This means inference time is \(\mathcal{O}(n)\) for sequence length \(n\). As such, it is much more time efficient than the standard transformer architecture.

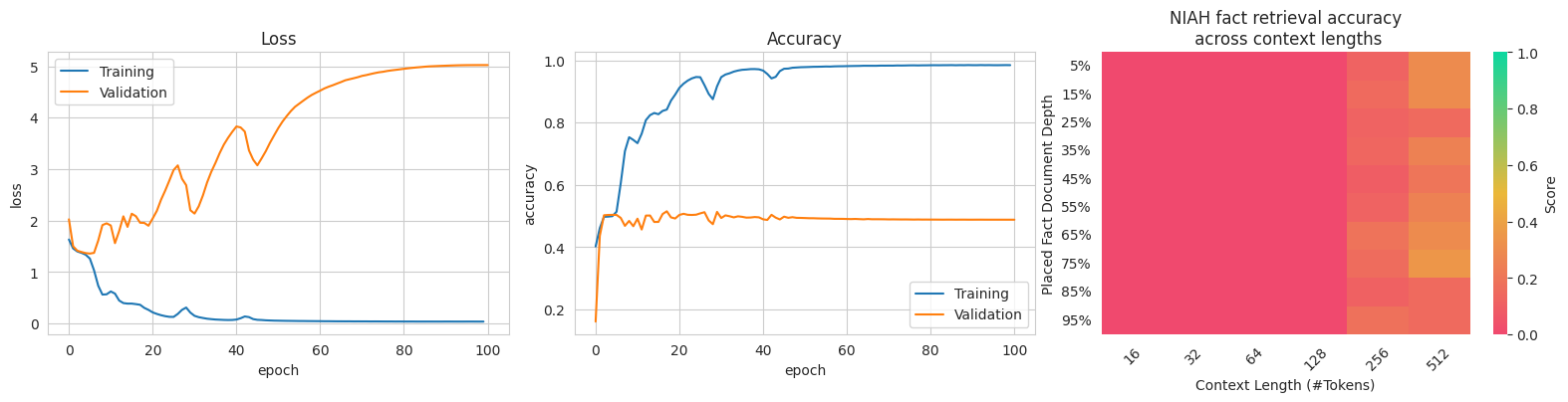

I replicated a Linformer and tested it on the datasets. It was unable to learn the language and constantly overfit. After significant experimentation, and repeating my experiments with the official implementation, I concluded that Linformer struggled to recognise even regular languages. Instead, Linformer consistently overfit to the training data and refused to approximate a DFA, even when provided extensive amounts of training data. I was unable to construct a situation where the Linformer approximated a DFA and did not overfit.

Linformer does not have a causal mask. I hypothesised that the lack of a causal mask meant that Linformer struggled to approximate the behaviour of a finite automaton. To test this hypothesis, I removed the causal mask from a transformer and tested its performance. I found that it caused a significant performance drop, however not to the same extent as the Linformer. From this, I was able to conclude that there is a significant gap between the langauges learnable by a Linformer and by a Transformer.

Sparse Transformers

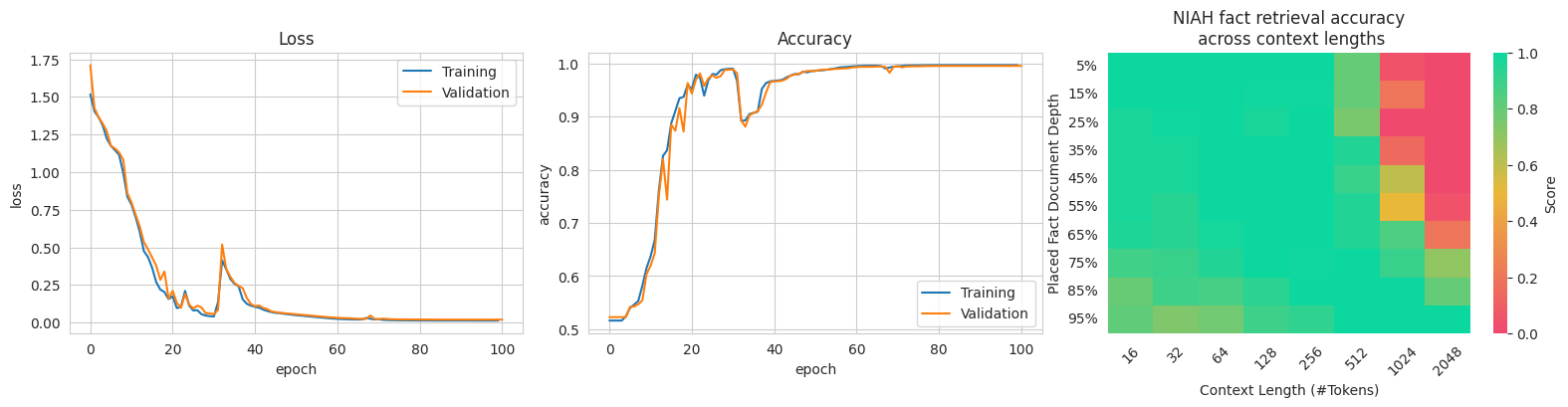

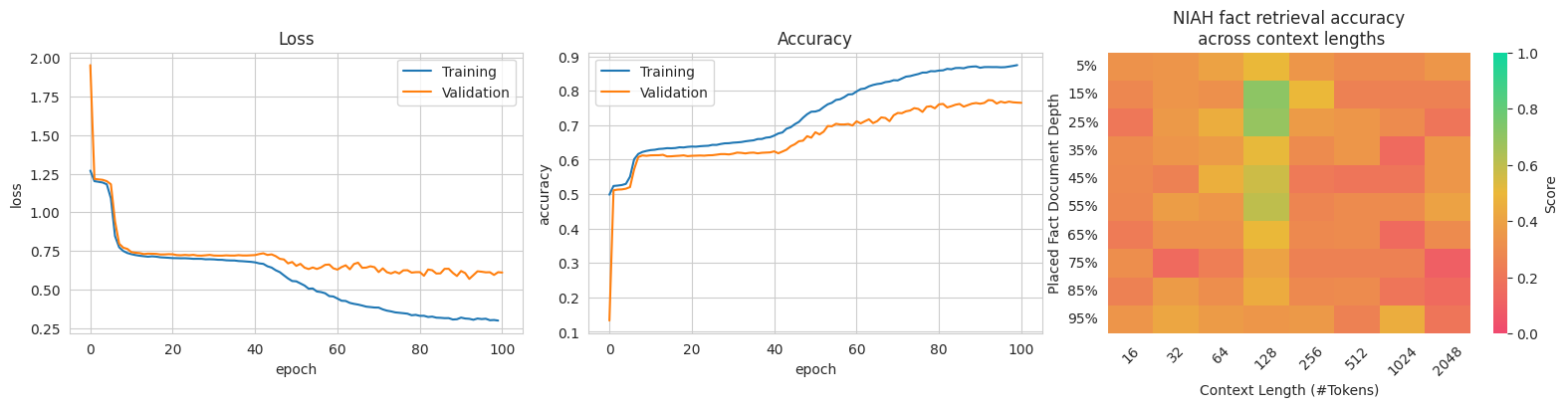

Sparse Transformers have time complexity of \(\mathcal{O}(n\cdot \lg n)\) for sequence length \(n\), which they achieve by limiting the flow of information.

I repeated the experiments above with Sparse Transformers. I found that due to the limited information flow, they required much deeper networks to propagate information in the same way as earlier. Transformers were able to achieve near-perfect accuracy on the regular language dataset with 3 layers. Sparse Transformers had such throttled information flow such that they would require 4 layers to propagate information to the next position. I was therefore only able to elicit performance out of 8-layer Sparse Transformers. This explicitly demonstrates how much less expressive Sparse Transformers (of fixed size) are than Transformers. Notably, I did not find Sparse Transformers to be fundamentally less expressive: they may be better suited for other tasks.

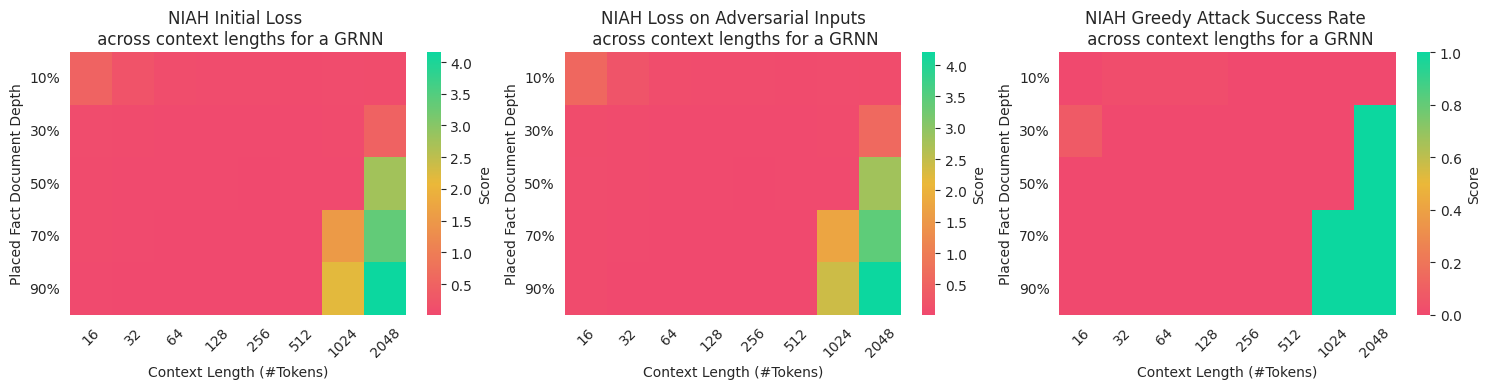

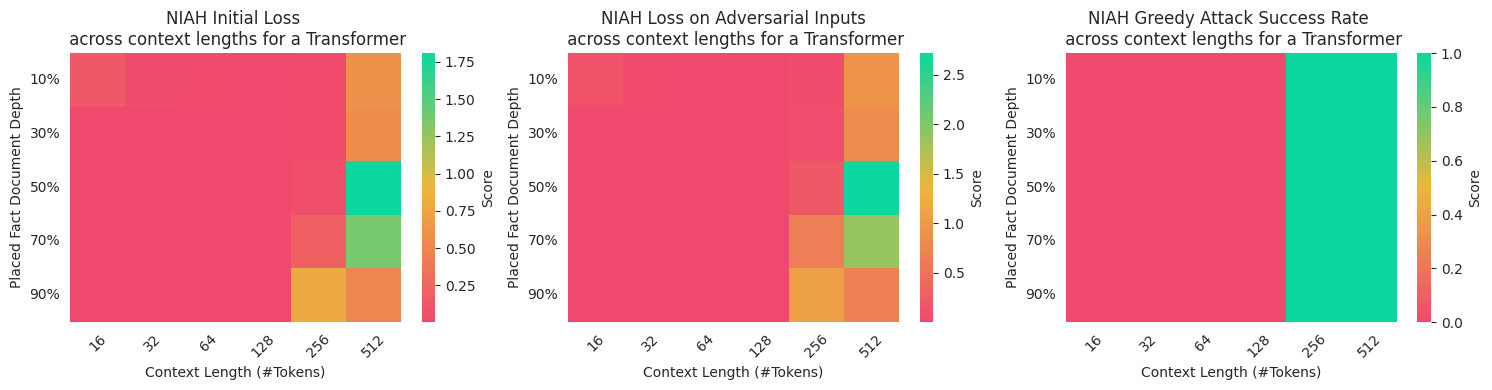

Sequence classification models learn robust approximations

I concluded by investigating the robustness of the approximations learnt on the regular language dataset. The theory is that if models learnt the actual function or a robust approximation, then adversarial attacks would be difficult to generate. However, if they learnt poor approximations, then adversarial attacks would be easy!

I found that black-box greedy attacks are easy. However, generating examples efficiently using white-box gradient-based methods proved ineffective. During my explorations, I implemented a greedy attack, Projected FGSM

I found that attacks which exploited gradient-information were unlikely to succeed. I attribute this to the discrete nature of the optimisation problem. Greedy attacks were able to succeed on both GRNNs and Transformers for longer context lengths. This implies that the models were able to learn the simple dataset and learnt robust approximations.

Conclusion

Overall, this project served to make the separation of theoretical expressivity and the learnable expressivity explicit. Additionally, it demonstrated how inductive biases help models to approximate finite automaton, which is demonstrated by GRNNs performing similarly to transformers in this situation, despite being outclassed by them in larger tasks.